Capital Markets allow us to trade where assets whose maturity is longer than one year are sold. These markets enable the firms and investors to raise capital to finance their long-term investment needs. For example, if a firm invests in the R&D of a new drug and then wishes to build a manufacturing plant for such medicine. Then, capital markets may help them to raise capital for longer periods. Similarly, these markets also enable the sale and purchase of mortgage-backed assets, which ensures the liquidity of mortgage markets. A liquid mortgage market means banks could generate extra cash to support individuals and families to borrow money to buy homes, office buildings, and other real estate. Capital Markets are not some specific geo-locations confined to one building. These Markets represent a broad set of financial agents interacting through the Internet, telephone, or any messaging service.

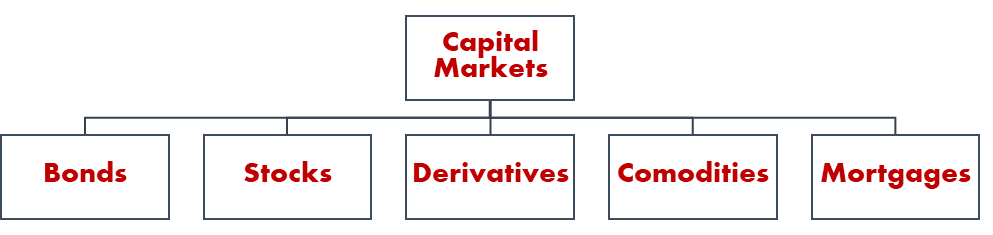

Capital Markets are defined by the type of assets sold in them. A generic categorisation of capital markets may be depicted below; it’s important to remember that these markets overlap. For example, mortgages are often securitised as Bonds and Bonds are often secured as mortgages.

Bonds

Financial Instruments to generate long-term financing.

Bonds are a debt instrument that enables firms, financial institutions, governments, and other institutions to raise debt capital for the long term.

| Accounting Treatment of Bonds: Bonds represent interest-bearing liabilities on an issuer’s balance sheet. Therefore, the issuer can deduct interest payments as an expense from their income. Hence, Bonds are regarded as a tool to save corporate taxes. They represent a yield-generating financial asset on a buyer’s portfolio. Therefore, the income is taxable and requires appropriate reporting. |

Bonds are fixed-income instruments with fixed interest payments over a specified period. Therefore, investors such as pension funds or individuals who need regular income at fixed intervals (i.e., annually or semi-annually) prefer to buy these instruments. Bonds are a liability and a cost for the issuer of a bond. They represent costs as they require the borrower to pay the attached coupon (interest rate) periodically, and failure to make such payment may result in default.

| Finance Treatment of Bonds: Besides the accounting treatment, the finance discipline views bonds as an indicator of leverage or Finance risk. Leverage indicates the indebtedness of a firm, and the higher the leverage higher the financial risk. Financial risk suggests the likelihood of a bond issuer defaulting or being unable to meet their obligations. |

Bond issuance and Parties: Bond issuance follows intensive financial reporting, communication, compliance, and auction process. Financial institutions such as banks and brokerages are crucial in facilitating bond launch. There are two main parties to a bond:

- Bond Issuers: These are firms, banks, financial intermediaries, government, and other institutions which issue bonds to raise capital for their financing needs. These issuers need to demonstrate that they have of following characteristics:

- Issuers are financially viable and have assets sufficient to cover bondholders’ principal payments in case of default.

- Issuers can generate sufficient income to pay interest payments accrued on bonds.

- Issuers enjoy credibility with the rating agencies or in the financial system. However, issuers with junk status (poor credit rating) can also issue bonds. For junk bonds, such issuers must offer very high interest rates.

- Issuers have sufficient corporate governance mechanisms to ensure that wealth is not transferred from bondholders to shareholders of the firms.

- Issuers have sufficient corporate governance mechanisms to ensure that wealth is not transferred from bondholders to shareholders of the firms.

2. Bondholders: These are market participants who invest in bonds. These investors may comprise investors, hedge fund managers, portfolio managers, banks, financial institutions, governments, and individuals. The purpose of investing in these bonds can be many folds:

- To earn a fixed income in the form of interest.

- To become part of the firm by having a secure investment. Bonds are more secure than stocks, as when a firm defaults, the bondholders are paid before shareholders.

- To have tax savings. Municipal bonds issued by governments and local governments are often exempt from tax. These bonds allow investors to earn interest income without incurring any tax.

| Who Buys and Sells the Bonds? | |

| Pension funds and Money Managers | Purchase bonds to generate fixed income to meet their obligations towards pension holders. Often, they sell their pension bonds to raise capital for further investment or invest in other bonds. |

| Banks | Banks purchase bonds to hold in their financial assets’ portfolio. These bonds earn regular interest income. Banks also buy safer bonds (e.g., AAA, rated) to deposit with the Bank of England. Banks also issue bonds to raise long-term capital. |

| Investment Banks | Help firms, governments, and banks to sell their newly issued bonds in the capital markets. They also purchase bonds as an underwriter. Being an underwriter, they guarantee that if all the bonds issued do not sell or the price falls below the agreed price, these banks will buy such bonds. |

| Types of Bonds: Bonds are customisable and, depending on the need of the issuer and requirements of borrowers’ bonds, can be reshaped to make them look interesting. Depending on the type of issuer, we can broadly divide bonds into two categories: 1. Government Bonds 2. Corporate Bonds In this article, we’ll mainly focus on Government Bonds and in the later article, we will analyse corporate bonds. |

Government Bonds

Treasury Notes, Treasury Bonds, and Gilts

These are issued by central governments such as the USA or UK. Treasury notes are issued for 1 to 0 years, and Treasury bonds have 10 to 30 years of maturity. Government-issued bonds (liabilities) that are indexed, linked or conventional and issued in £100 denominations. These instruments are considered “risk-free” because their issuers are sovereign entities that have never failed to make payments. The rate offered on them is generally very low and acts as a benchmark to assess the viability of risky investments. Often, the interest rate offered on these bonds is lower than the inflation rate, which makes the real interest rate on these bonds negative. However, investors still invest in these instruments because they are safe places to park excess capital.

TIPS and Index-linked Gilts

As the rates offered on government-issued bonds are often very low, the USA and UK governments also issue inflation-protected instruments such as Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) and Indexed-Linked Gilts. These instruments adjust the principal and coupon payments in line with the inflation rate (RPI) to account for the inflation effect and ensure that investors receive a return rate that covers inflation.

Stripped Bonds (Striping Treasury Bonds and Gilts)

Stripped Bonds (security) refer to security created after interest-bearing bonds are divided into “interest payments” and principal payments.

Imagine a bond with a 10-year maturity issued, and it pays 10% annual interest. If we strip it, we can create 11 securities comprising 10 yearly payments of interest and 1 last payment of Principal. These stripped bonds are “zero-coupon” and do not pay interest. US government, and in the UK, Gilt-Edged Market Maker (GEMM), Debt Management Office (DMO), and Bank of England (BoE) are allowed to strip bonds. Read further here.

Municipal (Muni) Bonds

Local governments issue muni bonds to finance their financing needs. The bonds enable the financing of local public projects such as roads, utilities, public services, and social services. Interest on these bonds is tax-exempt and often attracts tax-savvy investors. Local councils may issue such bonds by pledging future income from a project or without collateral. The first type is called income-protected bonds, whereas the later type is considered general obligations. These bonds are not default-free and require higher interest rates. To decide between taxable corporate bonds and Municipal, an investor needs to determine three things:

- Tax Differential indicates if the return on taxable bonds is higher than tax-free bonds. Investors can maximise their wealth by holding taxable bonds if it’s higher. The difference between the two rates may be estimated as:

![]()

![]()

- Yield ratios represent the ratio of tax-free rate to taxed rate and may be estimated as follows:

![]()

- Tax indifference indicates the tax rate at which investors are not bothered if they own Muni or normal taxable bonds. The cutoff point may be estimated as:

![]()

National Savings and Investments (NS&I) Bonds

NS&I Bonds are national savings issued by the UK government, offering citizens an easy, secure, and reliable way to store their wealth. As these bonds are protected against default; hence, the risk of default is minimal, and investors often can win tax-free prizes as well.

Default risk of Government bonds

The simple answer is no!

Although these bonds are protected instruments and default on them means that the issuer is either a country (USA, UK, Germany, Pakistan, and India) or a supernational organisation (EU) or a local government such (California or Manchester city council) is now financially not viable.

However, depending on the country or country, the default risk changes. For example, Pakistan is more likely to default than the USA. The UK has never defaulted, but in extreme cases, the government may decide not to pay its bondholder. Therefore, in this case, the risk is at the discretion of the Issuer. Generally, Municipal issuer is more prone to default as this enables them to transfer fiscal mismanagement costs to the bond investors. Further, these issuers make very few disclosures and are more prone to create adverse selection and moral hazard problems.

References

- Mishkin, F. S., & Eakins, S. G. (2019). Financial markets. Pearson Italia.

- Madura, J. (2020). Financial markets & institutions. Cengage learning.

- Pilbeam, K. (2023). International finance. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Fabozzi, F. J., Modigliani, F., & Jones, F. J. (2010). Foundations of financial markets and institutions. Pearson/Addison-Wesley.

- Kaufman, H. (1994). Structural changes in the financial markets: economic and policy significance. Economic Review-Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, 79, 5-5.

- Kaufman, H. (2009). The road to financial reformation: Warnings, consequences, reforms. John Wiley & Sons.

- Kaufman, H. (2017). Tectonic Shifts in Financial Markets: People, Policies, and Institutions. Springer.

- Hunter, W. C., Kaufman, G. G., & Krueger, T. H. (Eds.). (2012). The Asian financial crisis: origins, implications, and solutions. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Glushchenko, M., Hodasevich, N., & Kaufman, N. (2019). Innovative financial technologies as a factor of competitiveness in the banking. In SHS Web of Conferences (Vol. 69, p. 00043). EDP Sciences.

- Kaufman, G. G. (2002). Too big to fail in banking: What remains?. Quarterly Review of Economics & Finance, 42(3), 423-423.

- Kaufman, G. G. (2000). Banking and currency crises and systemic risk: Lessons from recent events. Economic Perspectives, 24(3), 9-28.

- Diamond, D. W., Kashyap, A. K., & Rajan, R. G. (2017). Banking and the evolving objectives of bank regulation. Journal of Political Economy, 125(6), 1812-1825.