Section 1: What is a Financial Market

Contemporary financial markets represent the mirage of human civilisation in which capital is exchanged between surplus and deficit parties at seamlessly and mutually agreed prices worldwide. The level of sophistication is such that trillions of $ are traded daily worldwide with clicks of a button between parties that may never come across each other. However, one wonders how these markets come into existence. The core of this market is formed due to the aggregate demand and supply of certain assets whose price is determined by the “collective behaviour” of participants. These participants come together to satisfy their financial needs; for example, businesses and individuals can broadly be described as cash surplus and deficit. The former seeks opportunities to invest, and the latter seeks investment to meet their financial needs.

Financial markets enable the cash deficit parties to issue stocks and bonds, write promissory notes, or even sell some asset-backed securities to cash surplus agents with an offer of interest rate or dividends. Financial Markets are the greatest marvel of modern times as they enabled mass capital movement nationally and internationally. Broadly, they allow:

- Securitisation of assets and liabilities: Stocks and Bonds.

- Commodification of capital: savings into investment

- Exchange of money between deficit and surplus agents: lender and & borrows.

- Exchange of information between investors and investees: through change of prices.

- Relay of government policy (interest rate notably): to the participants and the whole economy.

There are many other ways the FMs help our economy; however, those above are the most notable and will be our focus for this course.

Human behaviour and Financial Market (Behaviour Finance)

Financial markets are meeting points between cash surplus and cash deficit market participants. In finance theory, we may regard their interaction and its effect on asset prices as a “collective behaviour”. This behaviour determines the cost of these securities and, at best, represents the expectations of market participants about the price of a stock, bond, or issued security. Behavioural finance calls this “herd behaviour”, and it has been found that often, this leads to the irrational exuberance of behaving entities.

Why human behaviour matters in financial markets: In a free-market economy such as the UK, this behaviour underpins the prices we pay, wages we get, capital gains we make on our assets and economic growth we expect.

Composition of Financial Markets: Financial markets trade financial instruments such as stocks, bonds, T-bills, Eurodollars, Options, Futures, and swaps. Financial markets have 6 main elements:

- Financial Instruments.

- Active Buyers and Sellers include firms, banks, pension funds, hedge funds, individuals, and governments.

- Platforms of Exchange such as trading exchanges and Over-the-Counter facilitations.

- Regulators: to ensure the behaviour protects the interests of vulnerable parties.

- Stakeholders (highly debatable): directly and indirectly affected by financial markets.

Participants of Financial Markets: There are four major parties to financial markets:

- Financial institutions (banks, funds, and group investors).

- Non-financial institutions (firms).

- Governments.

- Individuals: wealthy individuals.

- Households: ordinary families.

Section 2: Types of Financial Markets

There’s no universal categorisation of financial markets. Instead, it’s the arbitrary division of financial markets. Financial Markets vary due to the nature of products, methods of placement, parties involved in exchange and duration for which firms need money. By placement, we mean the sale of securities, financial assets, or issues such as bonds, stocks, or promissory notes to public and private investors. Using the advice of their bank/broker/underwriter, a firm can choose whether to issue new shares as an IPO, sell the shares they previously bought back, trade the bonds they hold as an asset, issue new bonds, or raise capital from money markets for 1 to 365 days. The decision is a prerogative of firms but is determined by many factors such as interest rate, credit rating of the firm, existing debt-to-equity ratio of a firm, and market demands of a firm’s instrument.

Categorising Financial Markets

For simplicity, we may categorise financial markets as follows:

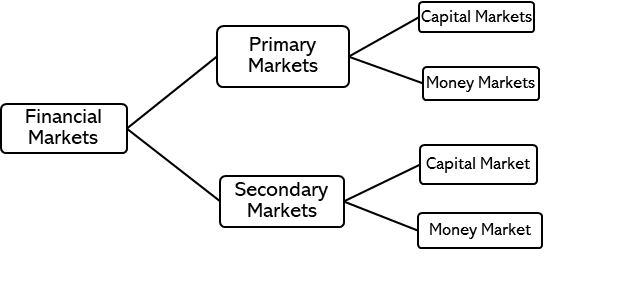

- Market types by “Instance of Placement”: It means if the instruments are issued for the first time (IPO) by an issuer, such as a firm or bank (like a brand-new car). Or it’s placed for sale by an owner of already already-issued instrument (like a second-hand car). Primary markets are where a financial instrument is issued for the first time (IPO), and usually, it’s organised by an underwriter through an auction method. However, when the same instruments are exchanged between investors after its issue, such a market is called a secondary market. The exchange happens between financial instruments between individuals, firms, banks, and financial brokers. It’s the latter type that we mostly engage with.

- Market Type by “Type of placement” means whether the sale of financial assets is made private or public. Often, security issuer issues their instruments or promissory notes only to a limited investor. This discrete market is called the private debt and equity market, and transactions mostly occur over the counter. However, certain investors may prefer to go public and issue their instruments to various investors, commonly known as public markets.

- Market Type by “Duration of Placement”: Another approach to define financial markets is the duration of issued instruments. If a security matures in less than one year, the market is called a money market, and if the security matures after more than a year, then the market is called a capital market.

- Market Type by “The platform of placement” Refers to how the instruments are exchanged between the parties. If the trade is made over the phone or through email, this resembles an OTC market. If the exchange is done via trade exchanges and bought and sold through publicly available platforms, we may call them trade exchanges.

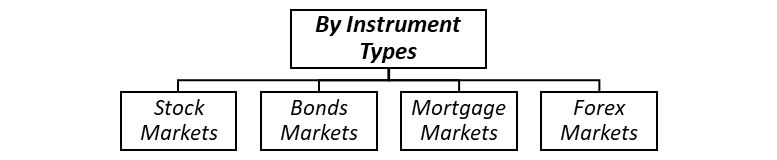

- Market Type by “Instruments of Placement”: Finally, financial markets are also defined by the devices they sell, such as bonds, stocks, mortgages, and forex.

Financial markets are conceptual constructs, and their existence is multifaceted. The diagram below captures one way of looking at them.

Understanding Primary and Secondary Markets, IPOs, and Capital vs Money Markets

| Primary Vs Secondary Market At the primary market, new issues of stocks and bonds are introduced; it could also be regarded as the market where the issuer of securities receives the proceeds from the sale of securities. An initial public offering is issued when companies sell securities for the first time. In secondary markets, the sale of previously issued securities takes place. |

| Initial Public Offering (IPO) IPOs are offered in Capital Markets – Where firms raise capital for their long-term needs. IPO refers to the sale or issue of financial assets for the first time. IPO is the public offering of stocks or the first listing of a firm’s shares. Firms IPO their shares through financial intermediaries. These shares are made available to the public; however, often, they are kept close to privileged large-scale investors such as big brokers. These shares are also offered to individual investors. IPO is also a privately held firm to become a public firm and be able to raise capital. It allows existing investors/founders to get the money for the company they have built or get more capital to invest in the expansion of their firm. 1. The market facilitating the IPO launch is called the primary market, and ex-post-IPO shares freely trade between investors in the secondary market. IPOs are not easy; they involve heavy costs attributable to compliance, regulatory requirements, fees, and transaction costs. Firms usually use a prospectus to inform their investors and gather as much demand as possible. |

| Capital Markets Vs Money Markets Financial markets (see the link for a detailed explanation of financial markets and their types: What is a Financial Market) are abstract concepts, and they represent a collection of buyers and sellers of financial assets who execute trades either directly or indirectly using a medium of telephone, internet, or other messaging and communication services. Financial markets are further divided into different types, given the Types and Variety of Financial Assets they exchange. One approach to categorise financial markets is using the time and duration of financial assets, i.e., short-term versus long-term. Based on the maturity duration of financial assets, we may divide financial markets into: 2. Capital Markets: Where assets whose maturity is longer than one year are traded. These markets enable the firms and investors to raise capital to finance their long-term investment needs. For example, if a firm invests in the R&D of a new drug and then wishes to build a manufacturing plant for such medicine. Then, capital markets may help them to raise capital for longer periods. Similarly, these markets also enable the sale and purchase of mortgage-backed assets, which ensures the liquidity of mortgage markets. A liquid mortgage market means banks could generate extra cash to support individuals and families to borrow money to buy homes, office buildings, and other real estate. 3. Money Markets: these are the markets where short-term assets are traded. These assets’ maturity date is less than a year. These markets help support firms and large corporations to either raise capital to meet their immediate liquidity needs or invest their surplus cash for better rates than banks for the short term. Money markets act as warehouses of money where large-scale borrowing and lending occur for periods ranging from a few hours to 365 days. |

Section 3: Money Market

What is a Money Market?

Money markets are avenues for trading short-term instruments such as treasury bills, Money Market Mutual funds, Commercial Papers, Certificate of Deposits, and Repos. These markets allow participants to create highly customised trades and instruments. Financial intermediaries often arrange these trades to meet the needs of their large clients, such as firms and corporations. These transactions do not occur in any location and are usually arranged by the traders over the counter. Therefore, this systemic market design that operates over the counter allows us to have a vibrant secondary market. Often, investors and investees exchange over the counter and try to use these instruments to meet their short-term financing needs to goals. Therefore, a high level of liquidity and the size of trades make the money market very important.

Money Market is a “misnomer”:

The term “money market” is a misnomer as it’s not a market where actual money notes are traded. A money market trades money-like instruments such as short-term bonds, T-bills, UK Gilts, Treasury Notes, and Commercial Papers. These instruments are short-term (from a few hours to 365 days) and have high liquidity. High liquidity means a financial instrument can be quickly transferred into cash by sale through an agent or on a public market. Hence, these instruments are considered as “Money”. These securities are:

- Sold in large denominations ($1,000,000 or more)

- They are short-term and usually issued by large firms and borrowers, so they have a low default risk.

- Mature in one year or less from their issue date, although most mature in less than 120 days.

Why does the Money Market exist?

You may ask why money markets exist and why not use banks to get finances for short periods. Banks, as financial institutions, have an information advantage: they have large cash holdings, usually have personal connections with the borrowers, and can track if the firm is using the money for stated purposes. The prime reasons for the money market as a preferred alternative are as follows:

- Money markets reduce transaction costs for lenders and borrowers.

- Operations through the money market do not result in additional regulatory, compliance, and capital management costs for the banks.

- The interest rate offered in the money market is unlike the bank rate. The difference is due to the regulation of the banking activities.

Importance of Money Markets:

The success of the money market stems from being a successful secondary market that facilitates a very large set of customers’ financial needs. Therefore, the well-developed secondary market for money market instruments makes the money market an ideal place for a firm or financial institution to “warehouse” surplus funds until they are needed. Similarly, the money markets provide a low-cost source of funds to companies, the government and intermediaries that need a short-term infusion of funds. These are the main purposes of money markets. Money markets are needed because revenues and expenses occur at different times. At times when there is no cash inflow, but corporations and the government need funds quickly, money markets provide an efficient, low-cost means of borrowing cash. We can summarise this discussion as follows:

- Money markets allow the warehousing of funds where firms and businesses with surplus cash can park their funds and earn interest rates on their excess cash.

- Money markets allow firms, banks, and governments to raise short-term funds by selling commercial papers, T-bills, asset-backed papers, and repos.

- Money markets allow firms to raise finances and their revenue and expenses mismatch.

- The money market also allows banks and firms to finance illiquid assets. Investors in Money Market: Provides a place for warehousing surplus funds for shorter periods.

- Borrowers from the money market provide a low-cost source of temporary funds.

- Corporations use these markets because the timing of cash inflows and outflows are not well synchronised. Maybe they have to make payments now, and they will receive the cash later. Money markets provide a way to solve these cash-timing problems.

Payment on Money Market Instruments

Most Money Market instruments do not pay interest. Instead, investors can buy them lower than the book price (par value). Par value is the value of the instrument when it matures. For example, a 180-day bond @ £100 each with an attached coupon of 3%. It may sell for £97 today, and the investor will receive £100 in 181 days and earn their 3% interest rate. To

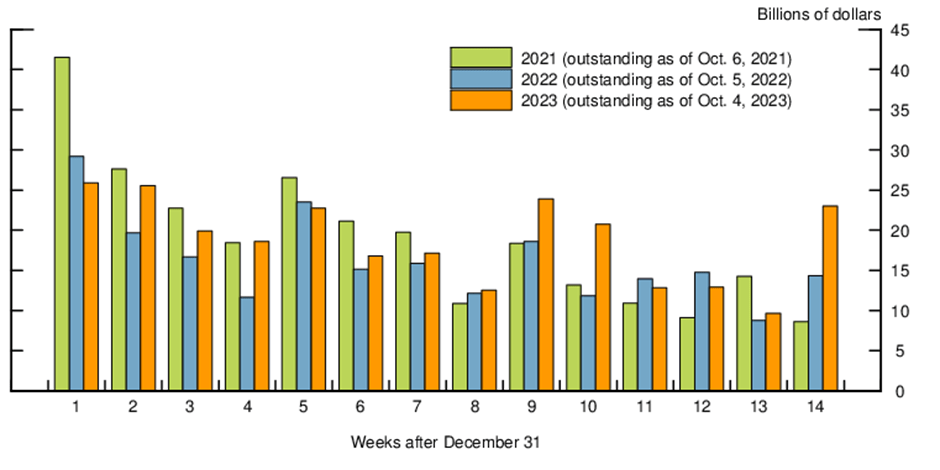

To further understand the money market instrument, consider accessing the Bank of England website. Money Market is a global powerhouse that helps firms to make payment domestically and internationally. Look at the graph below to understand the size of the US’s outstanding commercial paper (a money market instrument).

Source: Federal Reserve, accessed at this link: The Fed – Commercial Paper Rates and Outstanding Summary (federalreserve.gov)

References

- Mishkin, F. S., & Eakins, S. G. (2019). Financial markets. Pearson Italia.

- Madura, J. (2020). Financial markets & institutions. Cengage learning.

- Pilbeam, K. (2023). International finance. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Fabozzi, F. J., Modigliani, F., & Jones, F. J. (2010). Foundations of financial markets and institutions. Pearson/Addison-Wesley.

- Kaufman, H. (1994). Structural changes in the financial markets: economic and policy significance. Economic Review-Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, 79, 5-5.

- Kaufman, H. (2009). The road to financial reformation: Warnings, consequences, reforms. John Wiley & Sons.

- Kaufman, H. (2017). Tectonic Shifts in Financial Markets: People, Policies, and Institutions. Springer.

- Hunter, W. C., Kaufman, G. G., & Krueger, T. H. (Eds.). (2012). The Asian financial crisis: origins, implications, and solutions. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Glushchenko, M., Hodasevich, N., & Kaufman, N. (2019). Innovative financial technologies as a factor of competitiveness in the banking. In SHS Web of Conferences (Vol. 69, p. 00043). EDP Sciences.

- Kaufman, G. G. (2002). Too big to fail in banking: What remains?. Quarterly Review of Economics & Finance, 42(3), 423-423.

- Kaufman, G. G. (2000). Banking and currency crises and systemic risk: Lessons from recent events. Economic Perspectives, 24(3), 9-28.

- Diamond, D. W., Kashyap, A. K., & Rajan, R. G. (2017). Banking and the evolving objectives of bank regulation. Journal of Political Economy, 125(6), 1812-1825.